The History of Cyprus

The First inhabitants of Cyprus. Cyprus, the third-largest island in the Mediterranean, boasts a rich and complex history spanning thousands of years. Its strategic location between Europe, Asia, and Africa has made it a crossroads of civilizations. The story of the first inhabitants of Cyprus reflects influences from neighbouring regions while showcasing unique cultural developments. This exploration delves into the earliest periods of human occupation on Cyprus, from pre-Neolithic visits to the cultural transformations of the Neolithic and Chalcolithic eras.

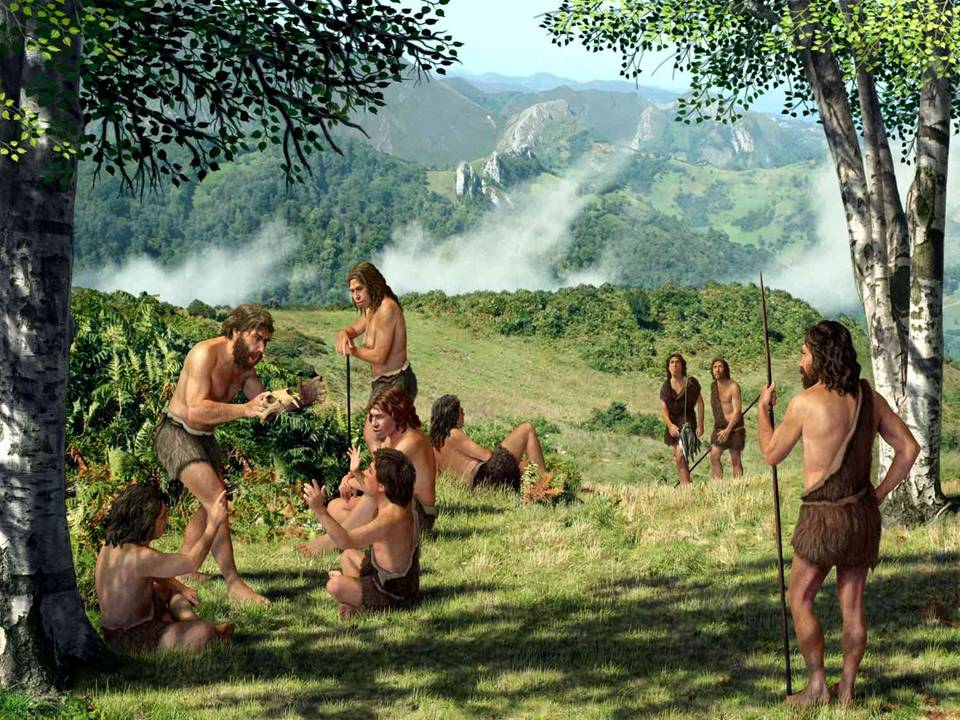

The Earliest Inhabitants of Cyprus: Pre-Neolithic Presence

Evidence of human activity on Cyprus dates back to the Epipaleolithic period, around 10,000 BCE. Archaeological discoveries, such as the Aetokremnos site on the southern coast, suggest that early hunter-gatherers visited the island. Aetokremnos, dating to around 8200 BCE, reveals signs of hunting and the exploitation of native pygmy hippos and elephants. These animals later went extinct, likely due to human activity and environmental changes.

These early visitors likely came from nearby regions,

such as Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) or the Levant. They had the technological capability to cross the sea but left little evidence of permanent settlement. It was not until the Neolithic period that more established communities emerged on the island.

The Neolithic Period

The Neolithic period marks the first significant phase of permanent human settlement on Cyprus, beginning around 9000 BCE. The earliest Neolithic communities belonged to the pre-pottery Neolithic era, before the development of ceramic technology. The Khirokitia culture, dating to around 7000 BCE, represents one of the most important archaeological finds from this period.

The Khirokitia site, located on the southern coast, is one of the earliest and best-preserved Neolithic settlements in the Mediterranean. It features circular stone dwellings built on terraces overlooking the Maroni River, showcasing a high level of planning and cooperation. The first inhabitants of Cyprus were primarily agriculturalists and herders, cultivating wheat and barley and domesticating sheep, goats, and pigs.

The transition from a nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle to settled farming communities marked a major shift in human society. Tools made from obsidian, likely imported from Anatolia, indicate early trade networks. Burial customs, such as burying the dead beneath home floors, suggest ritual or symbolic significance. The absence of fortifications points to a relatively peaceful society focused on communal living.

Chalcolithic Period: Cultural Development (circa 3900–2500 BCE)

The Chalcolithic period, or Copper Age, began around 3900 BCE. During this time, the use of copper emerged alongside traditional stone tools. Cyprus’s rich copper deposits made it a key player in early metallurgy. Sites like Lemba and Kissonerga in western Cyprus provide insights into this period.

Architectural changes, such as the shift from circular to rectangular houses, reflect increased social complexity. Larger communal buildings suggest more advance social

structures. Burial practices became more elaborate, with figurines of the “Mother Goddess” indicating the emergence of fertility cults and religious beliefs cantered on the natural world.

Bronze Age and the Dawn of Urbanization (circa 2500–1050 BCE)

The Bronze Age, beginning around 2500 BCE, marked a turning point in Cypriot history. The island’s copper resources became highly sought after, leading to increased trade with neighbouring civilizations like Egypt, the Levant, and Anatolia. This trade spurred the development of urban centres, such as Enkomi and Kition.

Bronze-working techniques, advances in pottery, and

textile production contributed to the flourishing of Cypriot culture. Contacts with the Minoans of Crete and the Mycenaeans of mainland Greece influenced Cypriot art, religion, and architecture. The Bronze Age laid the foundation for Cyprus’s role as a key player in the ancient Mediterranean world.

Cyprus Today

Today, Cyprus is home to a multicultural society primarily composed of Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots. Other communities, such as Armenians, Maronites, and Latins, also contribute to the island’s cultural mosaic. Understanding Cyprus’s inhabitants requires examining both contemporary demographics and the historical context that shaped their identity.

Greek Cypriots

Greek Cypriots make up 70–80% of the population. They are primarily of Greek descent and belong to the Orthodox Church of Cyprus. Their roots trace back to the Mycenaean Greeks, who arrived around the 12th century BCE. Greek Cypriot culture blends ancient Greek, Byzantine, and contemporary influences. Traditional music, dance, and cuisine play a central role in their identity.

Politically, Greek Cypriots have historically sought closer ties with Greece, a movement known as Enosis. This sentiment led to a violent struggle for independence during British colonial rule (1878–1960). The Republic of Cyprus, established in 1960, remains dominated by Greek Cypriots, though intercommunal tensions with Turkish Cypriots persist.

Turkish Cypriots

Turkish Cypriots account for 18–20% of the population. They are predominantly Muslim and trace their origins to the Ottoman conquest of Cyprus in 1571. Turkish Cypriot culture reflects Ottoman and Turkish traditions, with Islam playing a key role in shaping customs. The community celebrates both Islamic holidays and national days of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), a self-declared state in the north recognized only by Turkey.

The relationship between Greek and Turkish Cypriots has been marked by tension. In 1974, a Greek-sponsored coup aimed at unifying Cyprus with Greece prompted Turkey to invade the north, leading to the island’s de facto division. Efforts to reunify Cyprus continue, but the division remains a significant issue.

Other Minority Communities

Armenians: Armenians arrived during the Byzantine period and grew in number after the Armenian Genocide in 1915. They maintain their religious and cultural traditions, including the Armenian language.

Maronites: This Christian group traces its origins to Lebanon and arrived during the middle Ages. They follow the Maronite Catholic Church and speak a variant of Arabic.

Latins: Descendants of Venetian and Genoese settlers, the Latin community represents Roman Catholics with ties to Western Europe.

Migrants and Recent Communities

In recent decades, Cyprus has seen an influx of immigrants from Europe, Asia, and Africa. EU membership in 2004 facilitated movement from other EU countries. Migrant workers from the Philippines, Sri Lanka, and Africa, as well as refugees from Syria, have added to the island’s diversity.

Conclusion: A Complex and Diverse Identity

Cyprus’s population reflects its historical encounters with different civilizations. The co-existence and conflict between Greek and Turkish Cypriots have shaped the island’s modern political and social landscape. Despite divisions, a shared Cypriot identity, rooted in the island’s landscape, cuisine, and traditions, transcends ethnic lines.

The first inhabitants of Cyprus laid the groundwork for its rich cultural heritage. From pre-Neolithic hunter-gatherers to the agriculturalists of the Neolithic and the metallurgists of the Chalcolithic, each phase of early Cypriot history contributed to the island’s central role in the ancient Mediterranean world.