A Significant Discovery in the Annals of Cypriot History

The discovery of the terracotta army in Cyprus is a captivating tale that intertwines history, archaeology, and cultural heritage. This remarkable find, often overshadowed by other archaeological discoveries, holds a significant place in the annals of Cypriot history.

The Discovery

It was one Morning in the year 1929 when Papa Prokopios, the priest of the small Village of Ayia Eirini on Morphou Bay, was visiting his Field. To his surprise he found some looters digging in his field. The looters had uncovered fragments of ancient terracotta statues, hinting at a far greater treasure buried beneath the ground. Looting was very common at that time looking for treasures and selling them to the highest bidder. Papa Prokopios forced them out of his field.

Out of curiosity of the significance of the find, Papa Prokopios took one of the terracotta statues to the museum of Nicosia. One of the archaeological teams from the Swedish Cyprus Expedition showed instant interest and they were given the go-ahead to curry on the expedition. Led by Einar Gjerstad, the expedition swung into action, and by late 1929, archaeologists were hard at work unearthing figure after figure.

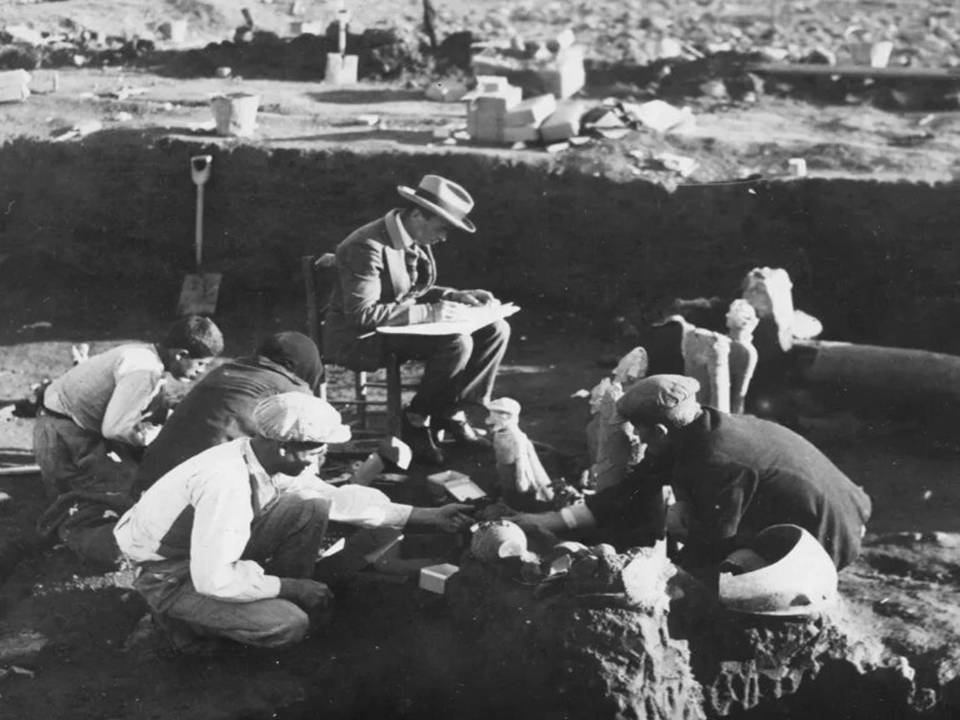

The Excavation

The excavation revealed a sanctuary used from 1200 B.C. to the end of the Cypriot Archaic period. Just half a meter below the surface, archaeologists discovered around two thousand terracotta figures arranged in semicircles. These figures depicted priests, warriors, commoners, and animals, with the largest ones standing life-sized. The meticulous arrangement and diversity of the figures showcased the artistic skill and cultural significance of the time.

The sanctuary evolved over centuries. Initially, it featured rectangular mud-brick houses on stone foundations, arranged around a central courtyard used for religious ceremonies. Cult objects such as offering tables, large storage jars, and terracotta bull figures filled the space, indicating a focus on agrarian deities. Over time, the sanctuary underwent significant changes, including the construction of a new sanctuary atop the old one, featuring an open temenos and a peribolos (priest’s garden).

Cultural Shifts and Abandonment

During the Cypro-Geometric III period, the sanctuary’s walls were raised, and a new altar was erected. Votive offerings evolved, introducing anthropomorphic figures and Minotaur’s, reflecting a growing anthropomorphization of the deity, now seen as a warrior divinity. The sanctuary peaked during the Cypro-Archaic I period, expanding to accommodate more structures, including enclosures for sacred trees, echoing Minoan culture. Bull-masked figures, likely priests, suggested rituals involving music, evidenced by figurines with tambourines and flutes.

Repeated flooding led to the sanctuary’s abandonment around 500 B.C. However, a brief revival occurred in the 1st century B.C., though on a smaller scale. The sanctuary fell into oblivion until Papa Prokopios unknowingly cultivated corn over the ancient terracotta sculptures. Looters, aware of the treasures below, led to the site’s rediscovery.

The Journey to Modern Museums

Despite the significance of the find, the then-colonial authorities struck a deal with the Swedish archaeologists. As a result, many of the terracotta figures were taken to Sweden, where they are now housed in the Medelhavsmuseet (Mediterranean Museum) in Stockholm. This has led to ongoing efforts to repatriate the cultural treasures to Cyprus.

Conclusion

The discovery of the terracotta army in Cyprus is a testament to the island’s rich cultural heritage and the enduring legacy of its ancient civilizations. The figures, with their intricate designs and historical significance, continue to captivate archaeologists and historians alike. The story of their discovery, excavation, and subsequent journey to modern museums underscores the importance of preserving and repatriating cultural heritage.

You May Also Like this

The Bad Stone in Kakopetria: https://anatolikilemesou.com/?p=4423

The Story of Berengaria Hotel: https://anatolikilemesou.com/?p=4303

Explore the History of Choirokoitia: https://fortheloveofcyprus.com/the-history-at-choirokoitia-cyprus-tourist-guide/

The Turkish Baths in Ktima: https://fortheloveofcyprus.com/the-turkish-baths-in-ktima-cyprus-tourist-guide/

The Archaeological Sites in Kato Paphos: https://fortheloveofcyprus.com/the-archaeological-sites-kato-paphos-cyprus-tourist-guide/

Roman History of Cyprus: https://fortheloveofcyprus.com/roman-history-of-cyprus/