Pachna Wine Village

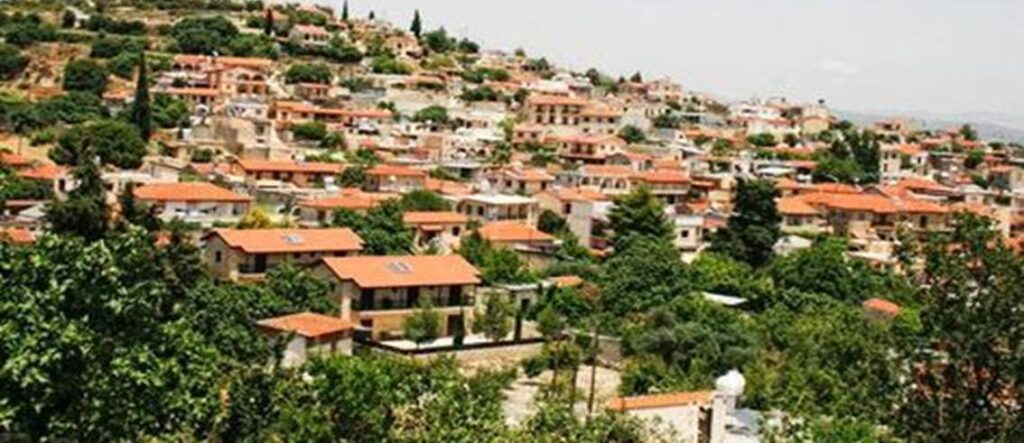

Pachna wine village sits in the foothills of the Troodos Mountains in Cyprus. It’s a hidden gem, rich in history and tradition. Known for its wine, Pachna has a story deeply tied to the island’s viticulture, culture, and resilience.

Ancient Beginnings and Early History

Pachna’s history stretches back to ancient times. Evidence suggests the area was inhabited as early as the Bronze Age. The fertile land and favourable climate made it perfect for agriculture, especially vineyards. Wine production in Cyprus dates back over 4,000 years, and Pachna played a part in this ancient tradition.

Ancient historians like Strabo and Pliny the Elder mentioned Cyprus as a major wine-producing region. Pachna, with its fertile soil, likely contributed to this legacy. During the Roman and Byzantine periods, Cyprus became famous for its sweet wine, Commandaria, one of the world’s oldest named wines. Pachna’s proximity to the Commandaria region and the Kouris River, which provided water for agriculture, supported its early growth.

Medieval Era and Ottoman Period

In the medieval era, Pachna wine village developed under the rule of the Lusignans and Venetians. Vineyards and olive groves expanded during this time. The Venetians, who ruled Cyprus from 1489 to 1571, took a keen interest in the island’s wine production. They likely improved winemaking methods in Pachna and nearby villages.

The Ottoman conquest of Cyprus in 1571 brought challenges. The Muslim-majority administration taxed wine production and limited its consumption. Despite these difficulties, the villagers of Pachna wine village continued their agricultural traditions. The village’s isolation in the mountains helped preserve its customs, including winemaking.

British Rule and Modernization

The British arrived in 1878, bringing changes to Cyprus and Pachna. They introduced modern farming techniques and improved infrastructure. Roads were built, making it easier to transport goods like wine. Pachna’s vineyards thrived during this period.

The 20th century brought more changes. New grape varieties and winemaking technologies emerged. However, this was also a time of social and economic upheaval, especially during Cyprus’s independence in 1960 and the intercommunal conflict that followed. Despite these challenges, Pachna’s winemaking traditions endured, passed down through generations.

Contemporary Pachna

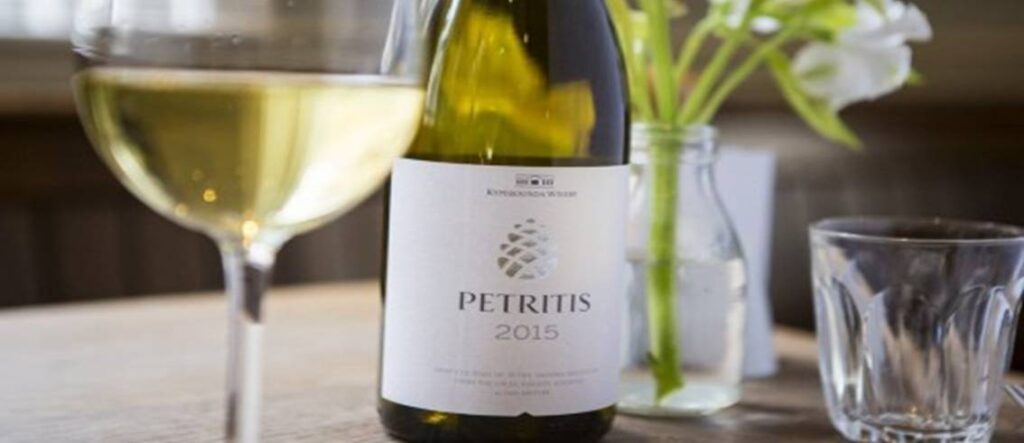

Today, Pachna wine village is part of the Limassol wine region, known for its high-quality wines. The village has embraced its winemaking heritage as a key part of its identity and economy. Traditional stone houses, narrow streets, and scenic vineyards give Pachna its charm.

Small family-owned wineries and larger establishments coexist in Pachna. They produce a variety of wines, including local varieties like Xynisteri and Maratheftiko, as well as international grapes like Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz.

The global interest in traditional Cypriot wines and sustainable farming has benefited Pachna. Wine tourism has grown, with visitors coming for tastings, vineyard tours, and festivals. The annual wine festival celebrates the harvest and attracts locals and tourists alike.

Conclusion

Pachna’s history as a wine village shows the resilience and adaptability of its people. From ancient roots to modern revival, Pachna has kept its identity as a centre of viticulture in Cyprus. Its wines, rich in history and flavour, tell the story of a village deeply connected to its land and traditions. Whether you’re a wine lover or a history enthusiast, Pachna offers a unique glimpse into Cyprus’s winemaking heritage.